Shock

Tuesday, October 15, 2019

arsip tempo : 171407390496.

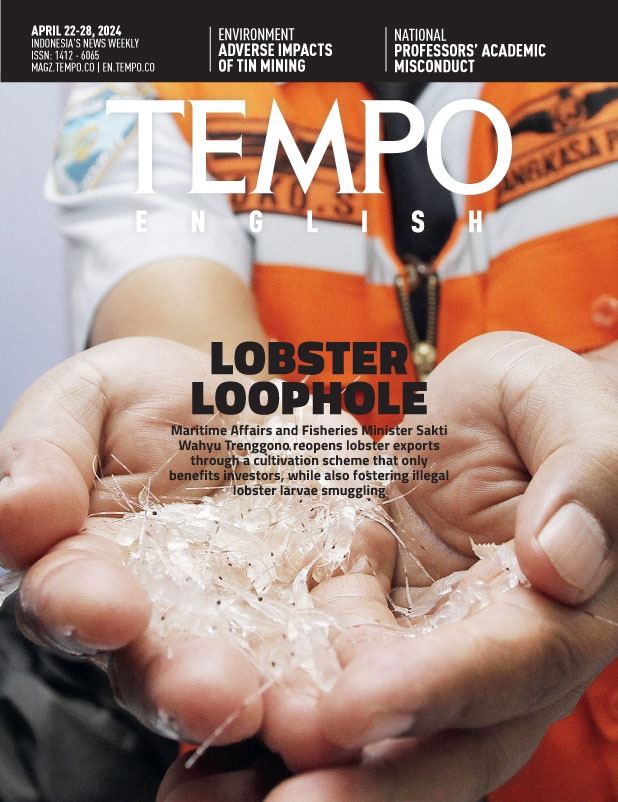

A YOUNG woman, standing among hundreds of demonstrators, wearing loose black sunglasses and an attitude of indifference but apparent conviction, holds up a large poster: “My crotch is not state property.” A pair of youg girls wearing hiljabs carry a different poster: “Something is standing erect. Not justice. Cocks.” Another young girl declares her thoughts in Javanese, translated as: “Is it true that matters of

...

Subscribe to continue reading.

We craft news with stories.

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More