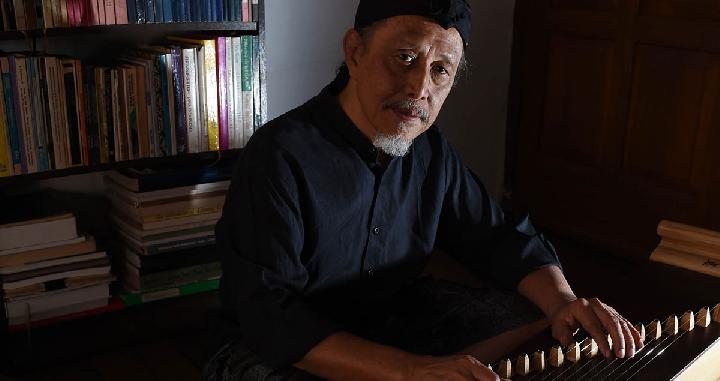

We Can’t be Dependent on Government

Monday, February 8, 2021

The traditional arts sector has been one of the most battered industry by the pandemic adversely affecting those who depend on stage performances for their livelihoods. Many traditional artists in rural areas have no choice but to turn into farmers, traders or online taxi drivers as they cannot rely only on government assistance to sustain themselves.

arsip tempo : 171360418767.

THE prolonged Covid-19 pandemic is threatening the survival of many traditional arts. Artists who make living from stage performances are among those who get the shorter end of the stick in the pandemic as demands for their services dried up. Without income and with welfare aid from the government hardly meeting their daily needs, much less to sustain their professions, a lot of traditional artists in rural areas have switched jobs to become farm

...

Subscribe to continue reading.

We craft news with stories.

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More