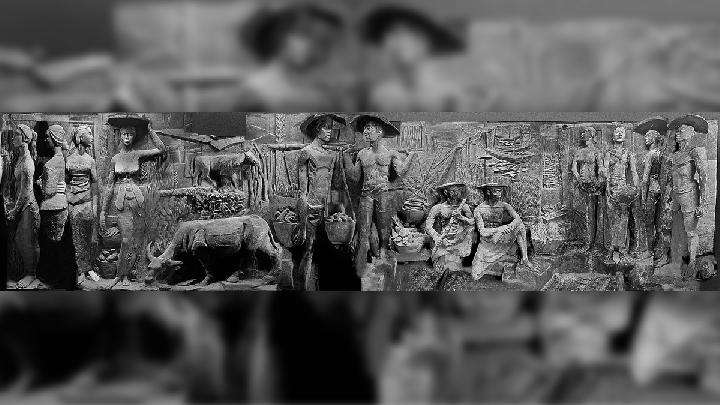

Who Made the Sarinah Relief?

Monday, February 8, 2021

Workers renovating Sarinah building last year found a relief from Sukarno’s era, 3 x 12 meters in size, hidden in the building’s electrical room. The relief depicts the atmosphere of the old market: women in traditional kebaya strolling the market and men in conical hats carrying wares. Records of the relief could not be found, leading to speculation from enthusiasts and experts regarding the origin of the relief and how it was abandoned in the building's generator room. Was the relief deliberately hidden by the New Order because it was deemed 'leftist' or did someone decide the depictions of the relief did not fit with the more modernized Sarinah?

Tempo interviewed children of famous artists from the 1960s to explore the possibilities of who made the relief. Tempo also interviewed the minister of manpower during the New Order era, Abdul Latief, who was an employee at Sarinah at the beginning of its establishment.

arsip tempo : 171391867851.

THE employee of the compact disc (CD) store on the first floor of the Sarinah building still remembers that day. One day, in 2005, a building maintenance worker was checking the building’s air conditioning and electrical panels. This is a routine maintenance job. The room where the electrical panel is installed is right next to the back wall of the music shop where he was working at that time, which is on the right side behind McDonald&rsqu

...

Subscribe to continue reading.

We craft news with stories.

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More