Cosmetic Preservatives in Long-Lasting Bread

Two bread brands are suspected of using a type of preservative that is not allowed in food. It is believed as a way to attack small and medium-scale bread producers.

Retno Sulistyowati

July 22, 2024

AFTAHUDDIN still keeps several Aoka and Okko brand breads. The Deputy Chair of the South Kalimantan Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Kadin) is perplexed by how bread that has been expired for several months shows no signs of mold.

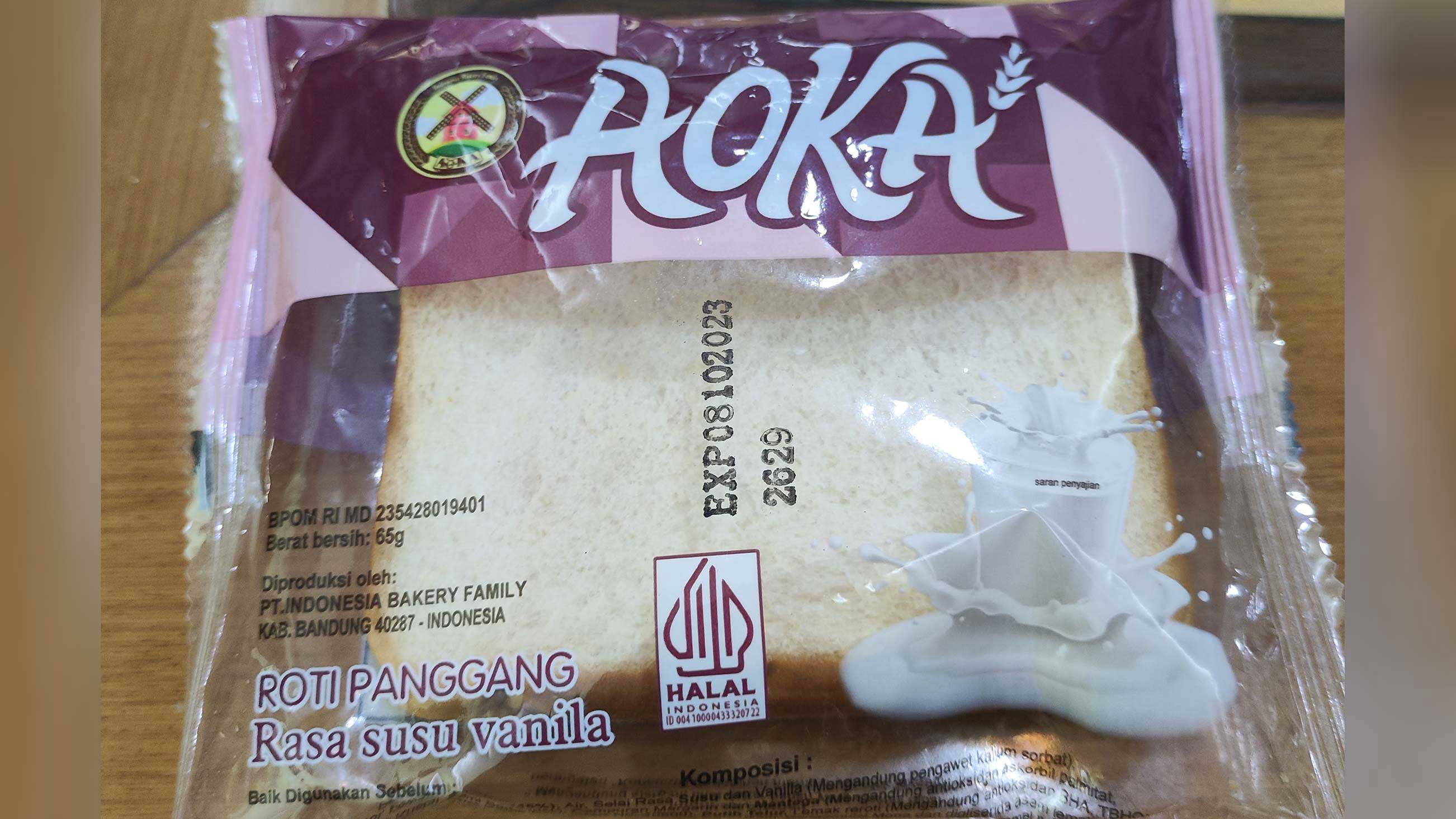

Aftahuddin, who also serves as Chair of the Borneo Bakery and Chicken Noodle Association (Parimbo), shared some photos with Tempo. One photo showed bread that expired on October 8, 2023, or nine months ago. “Its appearance is still good, with no black spots indicating mold,” he said on Friday, July 19.

He received reports from Parimbo members about the distribution of these breads in several traditional markets in South Kalimantan a few years ago. According to some of his colleagues, Aoka bread has been circulating in South Kalimantan since 2017. “It became more widespread during the Covid-19 pandemic,” he said. Small and medium-scale bread producers in Sulawesi, Maluku, Nusa Tenggara, and other regions also reported the presence of long-lasting bread in parts of eastern Indonesia.

Out of curiosity, Parimbo decided to have the breads tested in a laboratory. According to Aftahuddin, they sent bread samples to a laboratory owned by SGS Indonesia, part of the SGS Group, a multinational company providing laboratory verification, testing, inspection, and certification services. The test results shocked Aftahuddin and his colleagues because the Aoka bread sample was found to contain 235 milligrams of sodium dehydroacetate (in the form of dehydroacetic acid) per kilogram. Similarly, the Okko bread sample contained 345 milligrams per kilogram of the same substance.

Okko bakery factory in Solokan Jeruk, Bandung Regency, West Java, which has temporarily stopped production, July 17. TEMPO/Prima Mulia

Not satisfied with these test results, Aftahuddin and his colleagues tested two other types of bread for comparison. The brands tested were My Roti and Sari Roti. The laboratory results did not detect any sodium dehydroacetate in either of these brands.

Sodium dehydroacetate, also known as natrium dehydroacetate, is a preservative used as a food additive. Sugiyono, a professor of food science and technology at the Bogor Institute of Agriculture (IPB) University, West Java, explained that this chemical compound can inhibit microbial growth, thus preserving products. Sodium dehydroacetate, he explained, has a stronger preservative effect than other substances permitted by the Drug and Food Monitoring Agency (BPOM). However, “Some countries restrict its use in food,” he said on Thursday, July 18.

Acting Deputy for the Supervision of Processed Foods at BPOM, Emma Setyawati, echoed similar concerns. According to her, BPOM has not authorized the use of sodium dehydroacetate in food products, even though some other countries permit its use as a preservative within certain limits.

Regarding the presence of sodium dehydroacetate in two bread brands on the market, Emma admitted that BPOM has followed up on the report. She said that BPOM has tested for the presence of dehydroacetic acid, which is suspected to function as a preservative in these bread products. “We have conducted the tests, and the results showed that it was fine. These results came from our own laboratory,” she told Tempo on Wednesday, July 17.

Tempo sought responses from Indonesia Bakery Family, the producer of Aoka bread, and Abadi Rasa Food, the maker of Okko bread. According to Kemas Ahmad Yani, Head of Legal Affairs at Indonesia Bakery Family, the company does not use this substance in its products. “We have 16 types of products, all approved by BPOM,” he said on Wednesday, July 17.

Kemas stated that BPOM routinely conducts unannounced inspections at their factory. The most recent inspection took place on Monday, July 1. “If there were any issues, they would have been detected,” he said. Kemas noted that BPOM had made comments about the facility but stated that the raw materials and product formulas were deemed safe. “It is impossible for BPOM to overlook that.” Kemas added that the Indonesia Bakery Family’s team had traveled to Singapore and China for comparative laboratory tests.

Aoka products sold at a shop in Bogor, West Java, July 19. TEMPO/Ratih Purnama

Jimmy, the manager of Okko’s factory, also denied using sodium dehydroacetate as a preservative. However, he could not guarantee 100 percent, as the substance could potentially come from raw materials such as jams, butter, or cooking oil. “BPOM took samples of our bread from the market and our raw materials that are going to be produced.”

Jimmy recounted that BPOM conducted an inspection on Tuesday, July 2. “They came unannounced in the morning. I was not there, and the staff was surprised,” he said. During the inspection, Jimmy explained that BPOM took samples for testing. “This is a routine procedure for monitoring.” He also mentioned that BPOM’s inspection was related to the Good Manufacturing Practices for Processed Foods.

Regarding laboratory tests, SGS Indonesia’s management informed Tempo that they provide testing services for sodium dehydroacetate and sodium acetate in food products. These tests are conducted using standard methods AOAC 983.16 and LFOD-TS-T-SOP-8477 (Ref. EN 17294:2019). “These tests are relatively quick to perform,” said SGS Indonesia’s management on Thursday, July 18.

In their statement, SGS Indonesia explained that they are an independent service provider contracted by clients to perform testing, inspection, and certification based on specific needs. Test results are provided directly to the requesting party and are protected by confidentiality agreements. Therefore, when test result information was leaked, SGS stated, “Our name has been used without our permission by an unknown source to release confidential test report information.”

•••

INITIALLY, members of the Parimbo in South Kalimantan had no suspicions about bread products with an extended shelf life of over three months. According to Parimbo Chair, Aftahuddin, they actually intended to replicate the recipe. He wanted small and medium-sized bread producers in South Kalimantan to be able to produce products with the same shelf life.

For this reason, Aftahuddin and several other bakery owners from Kalimantan flew to China a few months ago. There, they were welcomed by a colleague who is also a bread producer. Aftahuddin and his colleagues expressed their desire to learn how to make bread with a long shelf life. They also informed the Chinese producer about the bread products they encountered in Indonesia that could last for months, while bread made by producers in Banjarmasin and surrounding areas could only last up to a week before mold began to appear. “We wanted to do a comparative study,” he said.

However, upon hearing Aftahuddin’s account, the Chinese bread producer frowned. According to the entrepreneur, bread that can last three months, six months, or even longer is not normal. “It doesn’t make sense,” Aftahuddin recounted what the Chinese baker said. The Chinese businessman suggested that the Parimbo members conduct laboratory tests to determine the preservative content in the long-lasting bread products.

Aoka brand bread that has expired (expiration date October 8, 2023) but does not have mold. Special Photo

Therefore, upon returning to Indonesia, Aftahuddin and the Parimbo members sought laboratory testing for several packages of the long-lasting bread. They sent samples to SGS Indonesia’s laboratory.

Parimbo’s efforts continued. From China, several members of the association flew to Japan. “We went there with our own funds,” said Aftahuddin. In Japan, they also met and talked with several bread producers. One of Parimbo’s questions was about how to make bread last for months.

Similar to the Chinese producers, the Japanese bread makers shook their heads. Seeing their reaction, Aftahuddin interjected, “Can we use sodium dehydroacetate?” The Japanese producers immediately exclaimed, “No, no, no.” Aftahuddin noted that the Japanese bread producers also mentioned that the use of this compound is dangerous and not permitted by the authorities.

Despite the concerns, the circulation of bread with unusually long shelf lives is becoming increasingly rampant in Indonesia. According to Parimbo’s tracking, there are 20 containers of such bread entering South Kalimantan each month. They are puzzled by the fact that this well-packaged bread is ending up in traditional markets rather than in convenience stores or modern retail outlets.

This is also why the local bread producers are protesting. Their market share is dwindling. Moreover, Aftahuddin said, the main consumers of their bread are children and fishermen, who need a lot of supplies when they go out to sea, and they now opt for bread that can last for months. “How will small businesses in South Kalimantan survive? They could go bankrupt,” he said. Motivated by these reasons, Parimbo is scrambling to find a solution.

It is not just South Kalimantan producers who are anxious. In Bandung Regency, West Java, where Aoka and Okko bread is produced, local home bakers are equally distressed. Factory products are infiltrating home-baking centers such as Gang Babakan Rahayu in Bojongloa Kaler subdistrict. According to Sutarno, also known as Nano, a manager of the Babakan Rahayu bread producer association, trucks deliver Aoka bread to the village daily.

The same situation takes place in Jakarta, Bogor, Depok (West Java), Bekasi (West Java) and Tangerang (Banten). Cheap, long-lasting bread floods traditional markets, including the early-morning cake market in Pasar Senen, Jakarta. Trisno, a bread producer, said how the market for small to medium-sized enterprises is being eroded by these durable breads. He explained that despite good technology, sanitation, hygienic processes, and packaging, bread cannot last more than six months. “The technology is expensive, but they sell the bread at very low prices.”

Aoka brand bread that has expired but does not have mold. Special Photo

But Trisno has his own strategy to combat the influx of long-lasting bread. He and his colleagues are promoting the consumption of fresh bread, meaning bread that has just come out of the oven, not bread that has been produced for months. “There are still people who prefer fresh bread.” Trisno said that his factory operates daily. He must carefully gauge market demand to ensure his products are sold out by the end of each day. So far, the bread produced by this Jakarta Provincial Government-supported business supplies several government offices.

Regarding the shelf life of their products, Okko bread’s producer has an explanation. According to Jimmy, the factory manager of Abadi Rasa Food, their bread can last up to 90 days due to their hygienic production process. He claimed the production area of his factory meets international standards. “It’s as sterile as a hospital operating room,” he said. The key, Jimmy adds, is in the packaging. “The packaging must withstand pressure up to 80 kilograms and must not be perforated or break.”

Therefore, when his products are questioned, Jimmy reacted. “This is very detrimental to us. Perhaps unhealthy business competition is trying various ways to undermine other bread producers.”