Little Women

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

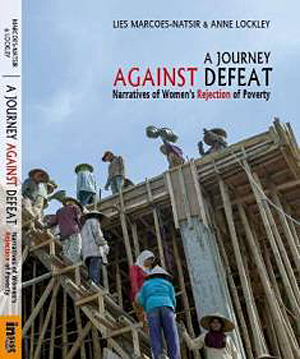

A Journey Against Defeat Narratives of Women's Rejection of Poverty

By Lies Marcoes-Natsir & Anne Lockley

Photographs by Armin Hari

Publisher: Insist Press, Yogyakarta

Social researcher Lies Marcoes-Natsir went on a nine-month journey to eight regions throughout Indonesia, and either with photographer Armin Hari or separately, stayed in each region for several weeks on end.

arsip tempo : 171408990534.

A Journey Against Defeat Narratives of Women's Rejection of Poverty

By Lies Marcoes-Natsir & Anne Lockley

Photographs by Armin Hari

Publisher: Insist Press, Yogyakarta

Social researcher Lies Marcoes-Natsir went on a nine-month journey to eight regions throughout Indonesia, and either with photographer Armin Hari or separately, stayed in each region for several weeks on end.

The two undertook a mission to explore the issues of poverty and translate

...

Subscribe to continue reading.

We craft news with stories.

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More