Capital Cities

Tuesday, September 10, 2019

arsip tempo : 171460015970.

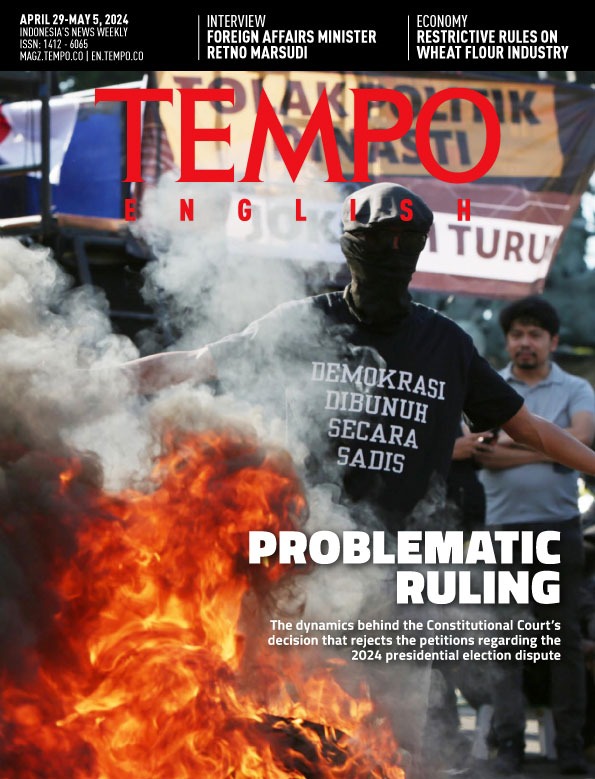

They are often replacement words indicating the place where justice is determined. But they are also often another word for the source of despotism and blunder. Or the opposite: the font of brilliance.

So it is with ‘Jakarta’, for more than a century it has no longer been the name of a place where people and objects reside. In certain discourse, it is not even concrete: not rows of stiff government buildings, proud monuments,

...

Subscribe to continue reading.

We craft news with stories.

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More