An Honor for an Old Javanese Literature Expert

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

arsip tempo : 171413240869.

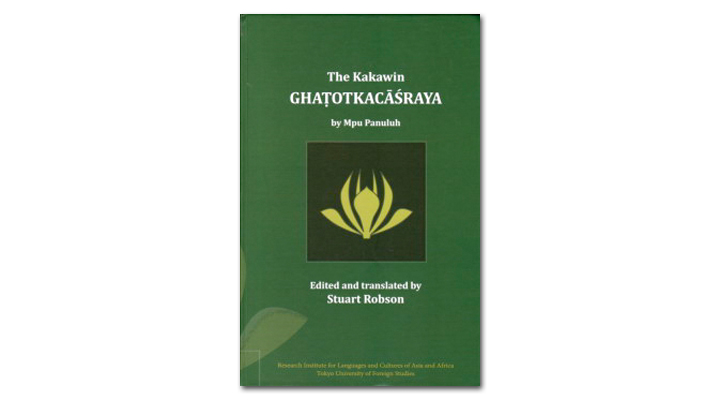

HE has dedicated his life to old Javanese literature. This tall man with a quiet demeanor from Australia is now 78 years old. He is Professor Doctor Stuart Owen Robson. In 1971, Robson published Wangbang Wideya: A Javanese Panji Romance, the result of his doctoral dissertation at Leiden University, the Netherlands. Robson is also known because he collaborated with Father Petrus Josephus Zoetmulder to make the monumental work Old Javanese-English

...

Subscribe to continue reading.

We craft news with stories.

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More