After the Pandemic: ‘The New Normal’

Tuesday, May 19, 2020

arsip tempo : 171417480487.

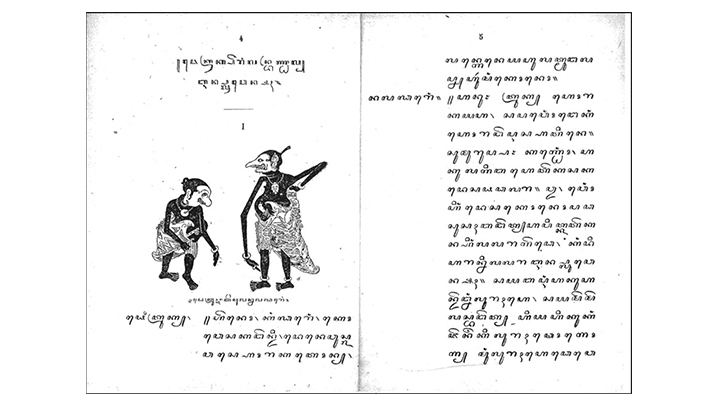

NOT a handsome face, nor a muscular physique. The only requirement to try capture Seriati’s heart was the ability to cure influenza. The contest announced by Seriati’s dad was worded thus: “Anyone capable of treating the dangers of this flu may marry my daughter, Seriati. Is she not a beauty, O Plump Master?”

The Plump Master admitted Seriati’s comeliness. He showed off his healing medicinal prowess against coughs a

...

Subscribe to continue reading.

We craft news with stories.

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More