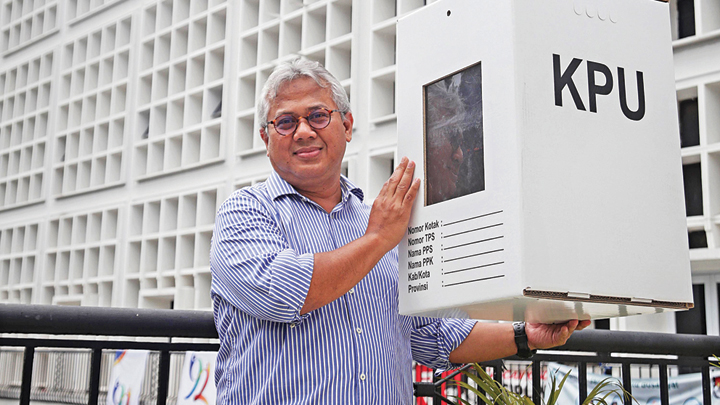

There Will be Bigger Risks if the Elections Are Delayed

Tuesday, November 3, 2020

arsip tempo : 171416262976.

AS soon as he was confirmed negative for Covid-19 on October 26, General Elections Commission (KPU) Chairman Arief Budiman returned to work immediately and step on the gas. Arief was hospitalized last September after being tested positive for SARS-CoVC-2 infection albeit showing no clinical symptoms and forced to stay away from his office for 35 days.

His swab tests taken during the hospitalization consistently came back positive. On the 20th da

...

Subscribe to continue reading.

We craft news with stories.

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More