In The Shadow of the Danantara Risk

Monday, November 11, 2024

Established to provide an opportunity to obtain loans, Danantara could sink Indonesia into a debt quagmire. Risk mitigation is key.

arsip tempo : 174669475996.

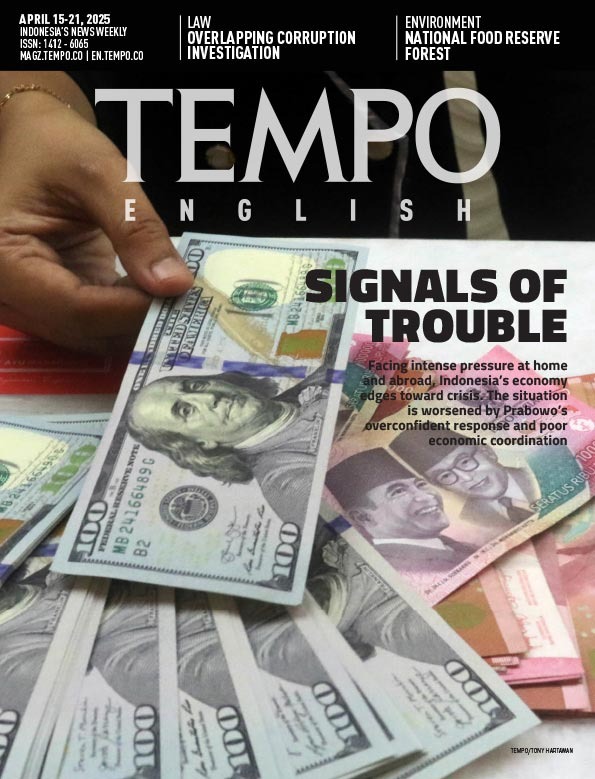

THE establishment of the Danantara Investment Management Agency by President Prabowo Subianto has given rise to a question: will state companies hived off from the State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) Ministry and then grouped under this new institution become more professional, transparent and free of political intervention? Or is there a threat of a new danger: by being too aggressive in seeking funds from mortgaging assets, Danantara could sink Indonesia into a debt quagmire.

Despite the claims that it will be similar to Temasek, the global investment company owned by Singapore, Danantara is actually more like Khazanah, the Malaysian investment body. While Temasek invests surplus government funds to generate substantial returns, Khazanah uses assets as collateral to seek investors. In other words, Danantara is an investment seeker like Khazanah, not a capital injector like Temasek.

In the first phase, Danantara will oversee seven of the largest state companies, namely Mandiri, BRI, PLN, Pertamina, BNI, Telkom and MIND ID, with total assets of Rp8,886 trillion. With the addition of the Indonesian Investment Authority, the state-owned investment management body, Danantara’s assets will be total Rp9,046 trillion. Subsequently, other state-owned enterprises and companies with special missions under the Finance Ministry, such as Sarana Multi Infrastruktur, will also come under Danantara, with the result that its total assets will exceed Rp15 quadrillion, or around 75 percent of Indonesia’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The government needs loans to pay for development. But the new loans in the State Budget will not be sufficient to cover the shortfall in the government’s budget, which has to be used to pay the principal and interest on existing and larger debts. Seeking investors by offering assets owned by companies under Danantara as collateral seems to be an instant solution.

But there is a potential danger: when there is an urgent need for funds, Danantara’s aggressive use of these assets to seek funding will invite potential disaster. Taking on loans exceeding the value of assets, in other words, being over-leveraged, carries a huge risk. This over-leveraging will reduce cash flow because some revenue will have to be used to pay interest. If the value of assets falls or revenue is insufficient, this over-leveraging could make it difficult to repay debts—which could in turn trigger the sale of assets, including by selling at a loss.

The establishment of Danantara is also an indirect way for the government to pay for flagship programs without going through the Finance Ministry. As it is directly under the authority of the president, Danantara could potentially be mobilized to cover the costs of programs or perhaps the political interests of Prabowo.

Therefore, seen from the macro economy perspective, Danantara could become a boomerang for Indonesia. So far, calculations of Indonesia’s debt ratio to GDP have only considered government debt, and not the debts of SOEs. This type of calculation could give rise to a false sense of security because it gives the impression that the debt ratio is still below 40 percent. However, if they are taken together, the debt ratio of the government and SOEs has already exceeded the safe level. From this perspective, Danantara is like papering over the cracks.

Danantara will have to simultaneously use a micro and macro approach. The Finance Ministry must be involved to a significant extent, especially in regard to risk mitigation. The bad practices that have been used by the SOEs Ministry, such as using government companies as cash cows, must be stopped. Handing out jobs in return for political favors will only give rise to mismanagement and waste.

Without careful risk mitigation, Danantara will only bring us to the verge of bankruptcy.