When Differently-Abled People Use Transjakarta Buses

Monday, October 14, 2024

Tempo accompanied several differently-abled people as they navigated public transportation in Jakarta.

arsip tempo : 174546990591.

IT is not easy for people with disabilities to travel independently using public transport in Jakarta. Tempo traveled with individuals ranging from blind persons to wheelchair users to observe just how inclusive the city’s transportation really is.

Maharetta Maha, who is visually impaired, can reach the nearest bus stop from her home on Jalan Raya Pos Pengumben in Srengseng, Kembangan, West Jakarta. However, she must cross two major roads and navigate an uneven sidewalk riddled with holes.

Using her white cane, she constantly swept left and right throughout her journey to detect any obstacles. “If I walk alone, it’s difficult,” she told Tempo on Wednesday, September 18, while walking on the sidewalk toward the bus stop.

The sidewalk lacked tactile paving—also known as guiding blocks—small bumps on the pavement to assist blind individuals. Without these, Retta—the nickname of Maharetta—could only guess the location of the bus stop. “There should be a sign or indication that helps us know where we are,” she said.

Two bus routes serve the stop, namely Transjakarta 8D (Blok M-Joglo route) and Mikrotrans Jak 53 (Grogol-Pos Pengumben). When Retta’s bus arrived, she slowly climbed aboard the small Transjakarta 8D bus. Though the bus was not crowded, all the seats were taken. A passenger stood up to offer Retta his seat.

The Transjakarta 8D route has 27 stops. Retta boarded at the ninth stop, planning to disembark at the 16th to transfer to a bus heading for Kebon Jeruk. However, since there were no announcements of the stop names, she became confused. “Where are we?” she asked.

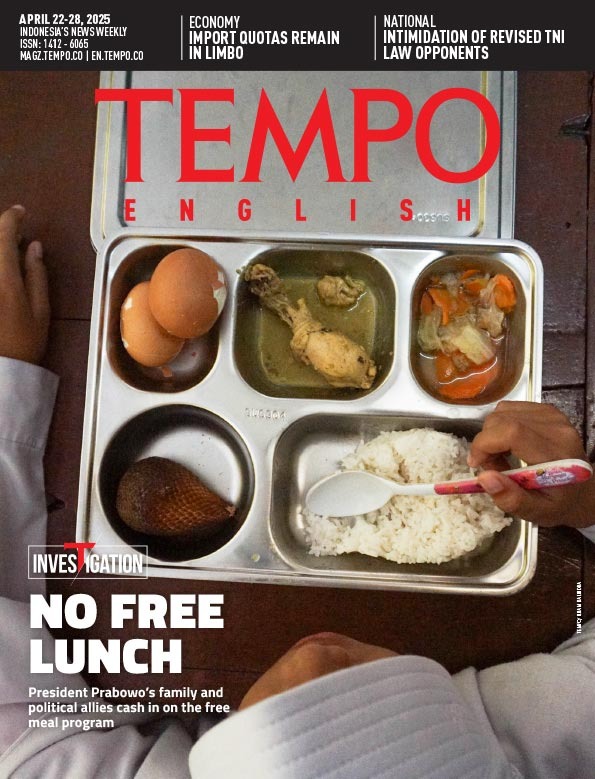

Visually impaired Maharetta Maha boards a bus at the Transjakarta feeder stop of Joglo Nurul Iman Mosque, West Jakarta, September 18, 2024. TEMPO/Ilham Balindra

When the bus stopped at her destination, it was too close to the entrance of the ITC Permata Hijau stop. Retta had to step cautiously onto the platform. A Transjakarta employee quickly assisted her, guiding her through the gate and onto her next Transjakarta bus.

Retta’s experience on Transjakarta Corridor 8, which runs from Lebak Bulus to Pasar Baru, was more pleasant. The stops were announced before each arrival. At the Kebon Jeruk stop, another staff member helped her exit the bus station.

Shortly after Retta left, another visually impaired passenger, Risma Ulyna, arrived. The 50-year-old had traveled over 20 kilometers from Tanjung Priok in North Jakarta, a two-hour journey, to the Anak Terang Ministri Foundation Home for the Blind in Kebon Jeruk, West Jakarta.

Risma said she was not worried about traveling alone because she knew the route well. “I attend community activities there twice a week,” she explained.

To reach her destination, she transferred to Mikrotrans Jak 30 on the Grogol-Meruya route. Around 9am, she boarded the bus and comfortably sat among the other passengers. After 10 minutes, she informed the JakLingo bus driver of her stop.

When the free bus reached her stop, the driver informed Risma. However, the bus was too close to the sidewalk, obstructing her exit. Risma paused for a moment, then took her folded cane out of her bag and used it to assess the condition of the road. She walked slowly along the sidewalk, which had many holes, before arriving at her destination, the home for the blind, where she was welcomed by many of her colleagues.

Damaged sidewalks were a common complaint among the blind individuals we interviewed for this report. Aldo Naldi Ramli, 65, explained that many sidewalks are uneven, full of holes, and lack tactile paving. If they are even, they are often blocked by street vendors or illegally parked vehicles. “The transportation is fine, but the problem lies with the sidewalks,” he told us at the Anak Terang Ministri Foundation.

Aldo, who lives in Ciputat, lost his sight 40 years ago due to an accident. He is accustomed to traveling alone. In addition to meeting with members of the blind community, he offers massage services and trains aspiring masseurs. “My students are not only those who cannot see,” he said.

Aldo spoke about his experiences accessing public transport in Jakarta and the surrounding regions, from Transjakarta and the KRL Commuter Line to the Jakarta MRT. He noted that government-owned public transportation is improving, particularly with the addition of facilities for differently-abled people, such as free access to all Transjakarta services. He obtained his first free travel card at the Transjakarta office in Cawang, South Jakarta, in 2017, and renews it every year at Jakarta Town Hall.

His favorite Transjakarta routes include Corridor 8 (Lebak Bulus-Pasar Baru) and Corridor 13 (Puri Beta Ciledug-Tendean), which he uses frequently. He knows many of the staff at the bus stops along these routes, and they recognize him. The Kebon Jeruk stop on Jalan Panjang, West Jakarta, is one of his favorites due to its accessible layout and more attentive staff. “They’re all familiar with us from the home for the blind because we often use this stop,” he said.

His other favorite stops include the integrated CSW stop in South Jakarta and the Juanda stop in Central Jakarta, where there are many friendly staff members.

On that day, Aldo was using the Kebon Jeruk stop. He disembarked from Transjakarta Corridor 8, which departs from Lebak Bulus, and then switched to Mikrotrans Jak 30, heading for the home for the blind.

Aldo believes that the service provided at Kebon Jeruk should be the standard across all Transjakarta bus stops, as staff in other locations are sometimes disrespectful to people with disabilities. He referred to these individuals as ‘particular’. “These particular individuals assist people by pulling on their clothes instead of holding their arms,” he said.

Maharetta Maha rides a Transjakarta bus, September 18, 2024. TEMPO/Ilham Balindra

Aldo had a negative experience with a staff member who was not friendly toward blind people. Although he was being guided, the staff member’s position was incorrect, which made it difficult for Aldo to navigate with his cane. “So, I stepped on a hole,” he said. He noted that many people he knows have had similar negative experiences because staff members do not understand the proper way to assist blind individuals.

He also has stops on his blacklist, such as Tomang, which is small, full of steps, and often lacks staff, and the Sunter Utara stop, which has no staff and complicated access. “It’s dangerous for blind people who walk alone and are unfamiliar with the area,” Aldo said.

Another common issue is buses that do not stop exactly in front of the door. As a result, blind individuals often do not realize there is an obstacle in their path. Aldo once nearly collided with a pole while disembarking from a bus. “Luckily, another passenger pulled me back. At the time, there were no staff available to assist me,” he said.

Despite these issues, Aldo has high praise for the KRL Commuter Line, which he uses to travel from Juanda station in Central Jakarta to Depok or Citayam in West Java. He finds the staff of the Kereta Api Indonesia subsidiary friendly and helpful.

As soon as he enters the station, an employee at the gate would ask where he is going, and another staff member accompanies him to the train. He was unable to comment on the service of the Jakarta MRT because he has only used it twice during the trial period in 2019.

On another occasion, Tempo accompanied a wheelchair user, Fitrina, on an MRT trip from the Hotel Indonesia Roundabout station to Lebak Bulus. A colleague helped her board the train as no staff were available to provide a boarding ramp. “Sometimes there’s a ramp, sometimes there isn’t,” Fitrina remarked.

At Lebak Bulus station, a staff member helped her disembark. However, Fitrina faced another inconvenience when she wanted to use the elevator to go down. She had to wait a long time due to a long line of people, and many passengers rushed for the lift as soon as they disembarked from the train.

Yurlina, another wheelchair user, has also experienced difficulties with lifts. The 50-year-old lives in Cililitan, East Jakarta, and uses the Transjakarta service from Cawang together with an assistant. She noted that many stops lack lifts. “For example, there are lifts in some places, but not in others,” she said when Tempo contacted her.

Lifts are essential for wheelchair users. Yurlina noted that the lift at the Cawang UKI stop has been out of service for a long time and remains unrepaired. At other stops, sloping platforms are risky for wheelchair users.

Despite these shortcomings, Transjakarta remains a crucial mode of transport for elderly passengers like 60-year-old Supono, who works as a parking attendant in Pondok Labu, South Jakarta. Every day, he travels from his home in Klender, East Jakarta by Transjakarta bus. “I have to change bus eight times,” he said.

Tempo traveled with him from the Blok M stop in South Jakarta one day in September this year. Shuffling along, he raised his hand to signal the Transjakarta Blok M-Kota number 5C bus, which was just about to pull away. The driver, noticing the elderly man stumbling, reopened the bus door. Supono rode the chilly, air-conditioned bus to Monas, then continued his journey on another Transjakarta 5C bus, heading for the Cililitan Shopping Centre (PGC) in East Jakarta.

“All the Transjakarta facilities are pretty good,” said Supono. He enjoys using public transport more now because he has a special senior card, which allows him to travel for free.