Social Forestry’s Illegal Fees

Non-governmental organizations assisting social forestry farmers are collecting fees for processing permits. The money in circulation may exceed Rp300 billion.

Erwan Hermawan

October 3, 2022

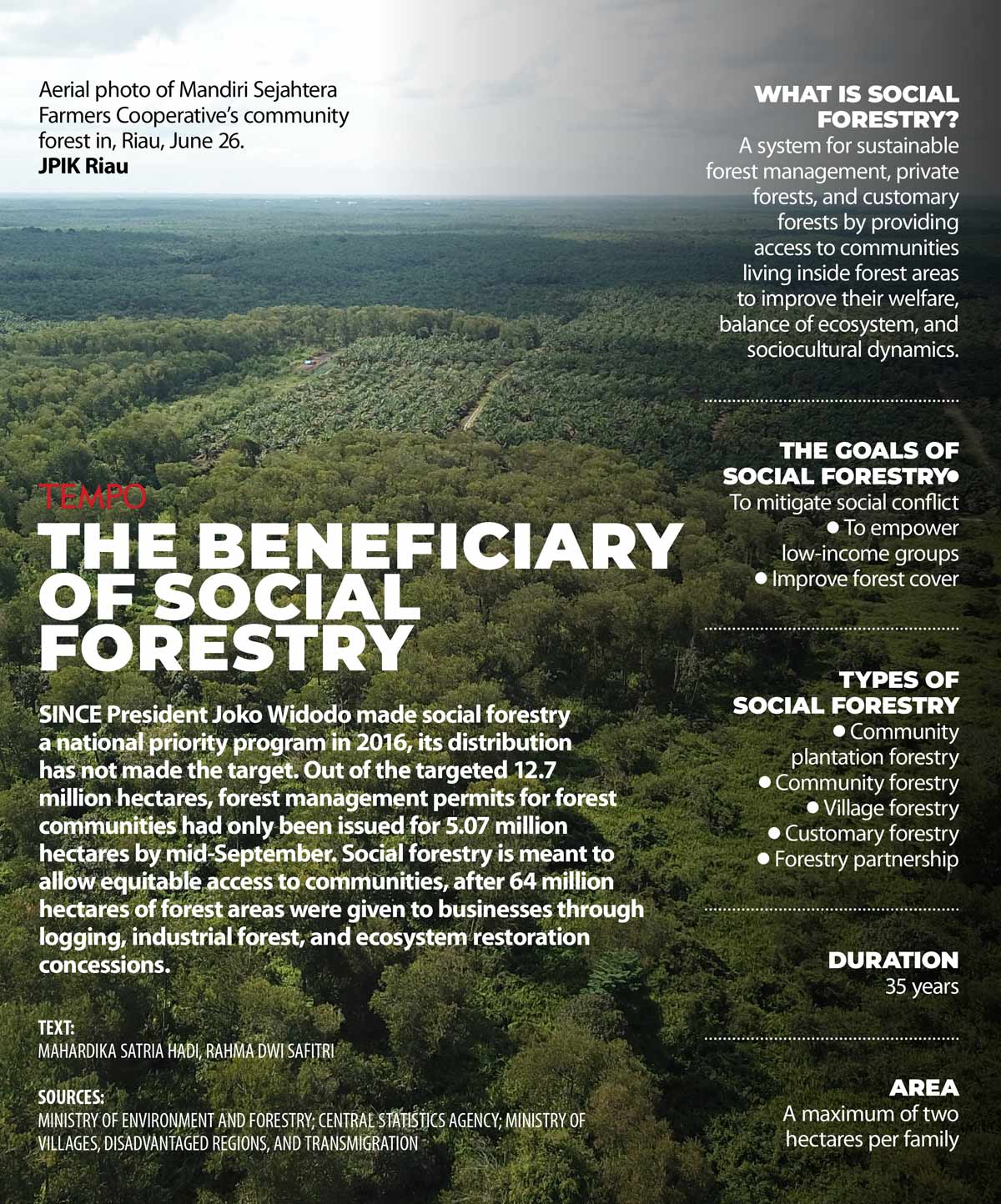

Social forestry has been a national priority program since 2016, with a total area of 12.7 million hectares. Communities around and within government forests may apply for permits to manage forests with a maximum area of two hectares per family. Requirements include being a member of a farmers group and receiving training from forestry trainers, non-governmental organization activists, or forestry professionals. Despite the program being free, in Java, the facilitators have been collecting illegal fees from farmers. In Sumatra, an industrial forest company legitimizes deforestation by exploiting a social forestry permit.

***

IT has been four years, but Sumila still remembers how hard she had to work to come up with the Rp500,000 requested by the Sukobubuk Rejo Agroforestry Farmers Group (KTH Sukobubuk). The money was a requirement for the 65-year-old woman to remain as the group’s member and to be allowed to manage the government forest 4 kilometers from her home in Bermi village, Gembong Subdistrict, Pati Regency, Central Java, through the social forestry program.

KTH Sukobubuk’s administrators argue that such fees are used to fund operations and administrative works. Sumila did not have any money. She worried that she would not be able to pay the fee and could no longer work the 2,500-square-meter forest that her family had always relied on. “My kid had to borrow money from work at Indomaret,” Sumila said, crying, on Friday, September 9.

The land Sumila manages belong to the state-owned forestry company, Perum Perhutani. Residents in Gembong subdistrict have been working the land to meet their daily needs. But, because the land belongs to the government, Sumila’s work planting cassava and corn in the area was considered illegal. She was labeled as a poacher. Yet, Perhutani could not keep her and local farmers away because of the potential social conflict.

A local resident points to a marking for sugarcane planting program initiated by state forestry company Perhutani in Pati, Central Java, September 7. TEMPO/Erwan Hermawan

In 2016, deforestation by villagers such as Sumila was legitimized through the social forestry program. The government provided 12.7 million hectares of government forest to be managed by local communities, including those who had already been cutting trees as well as new farmers.

Most social forests are former concession areas managed by timber companies and industrial forestry companies. In 2018, a social forestry program was created in the form of conservation partnerships through agreements between farmers and national park offices. Social forestry management lasts 35 years, with each family managing a maximum of two hectares, which may be inherited. Social forestry land, however, cannot be transferred to another person besides family members or used as collateral for a loan.

Sumila’s Perhutani land in Bermi village lies on a production forest. To prevent land conflicts, the social forestry program can legitimize the agriculture work performed by Sumila and other villagers, as long as they are joined under a farmers group. KTH Sukobubuk has 150 farmer members, led by Saman, who is chairperson of the Indonesian People’s Movement for Social Forestry (Gema PS) Foundation, a social forestry organization based in Central Java.

Farmers working in the social forestry area managed by the Sukobubuk Rejo Farmers Association in Pati, Central Java, in 2020. KTH Sukobubuk Rejo Doc.

Gema PS is a non-governmental organization (NGO) that assists social forestry actors in Java. The government requires all agroforestry farmers groups to receive assistance. If there is no assistance from the government, assistance may come from NGOs, universities, or forestry professionals.

Gema PS, led by Siti Fikriyah Khuriyati, a 2019 legislative candidate from the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), claims to have assisted 100,000 farmers in Java joined under 250 farmers groups. San Afri Awang, Environment Ministry’s Director-General of Forestry Planning and Forest Environment in 2015-2017, was a patron.

Siti Fikriyah claims her organization has already applied for a social forestry permit for 60,000 hectares, most of which is in the Perhutani area because of Gema PS’s focus is in Java. Unlike outside Java, Perhutani has two social forestry types: social forestry management permit (IPHPS) and forest partnership recognition and protection (kulin KK).

The differences of IPHPS and kulin KK lie in their types of partnership and levels of deforestation. Under an IPHPS scheme, remaining forest cover has usually declined to 10 percent, and IPHPS permits are issued by the forestry ministry. Meanwhile, kulin KK forests are still in good shape and partnerships are in the form of joint ventures between farmers and Perhutani.

KTH Sukobubuk, with 1,400 member farmers, received an IPHPS in July 2018. One month later, in a circular Saman asked each KTH member to submit Rp500,000. With uncertain earnings from corn and mere Rp1 million from each cassava harvest, Sumila did not have the amount requested. “If the yield is bad, (I) can only get Rp100,000 per harvest,” she said amid persistent sobs. In the circular, Saman threatened farmers who failed to pay the fee with expulsion from the KTH.

Unlike Sumila, Trishadi chose not to pay despite the request and threats from KTH administrators that he would not receive any social forestry concession. He said he was not afraid that his 5,000-square-meter land would be taken over by other farmers. However, last year, the 67-year-old farmer paid KTH administrators four times the amount requested, or Rp2 million. “This is the only land I have,” he said.

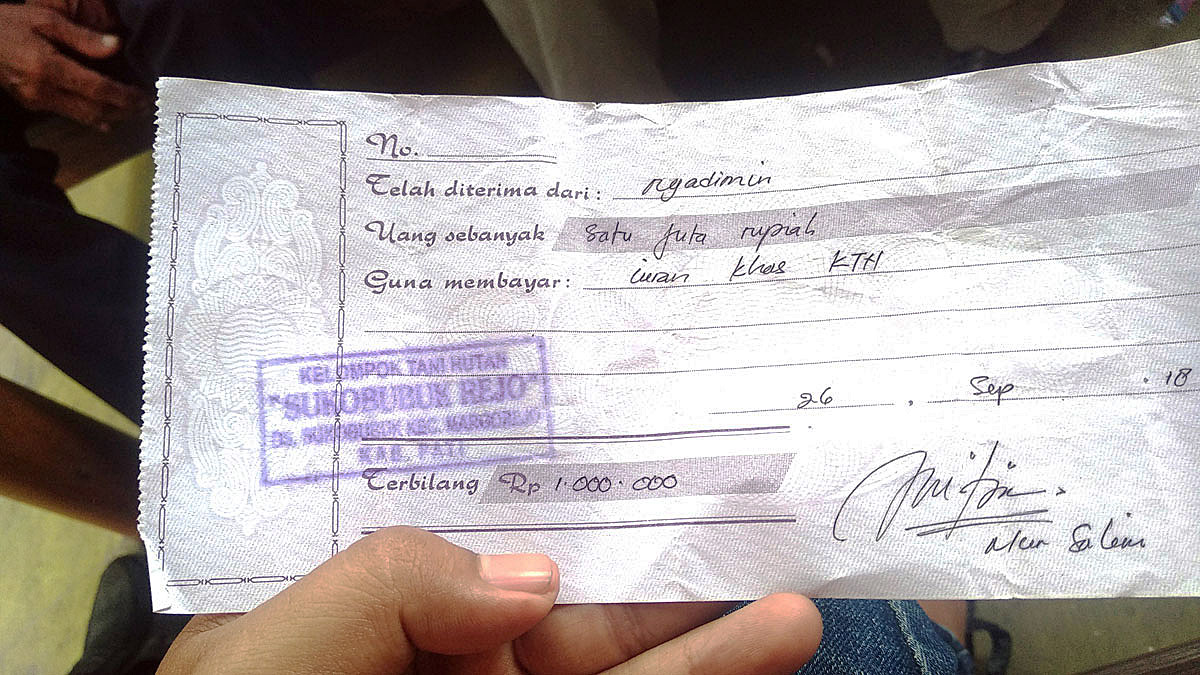

Faturrahman also paid Rp2 million. The 47-year-old man confirmed the invoice Tempo showed him. “I paid late, so there was a kind of fine,” he said. Likewise, Muhammad Solihin paid Rp1 million in 2018. But he was required to pay non-tax revenue (PNBP) in the amount of Rp104,000 in the following year. “At the time, my harvest failed because of rats,” said Solihin.

Saman denied that there have been illegal fees demanded from KTH Sukobubuk members for the sake of social forestry program. According to Saman, the fees of Rp500,000 to Rp700,000 submitted by the KTH members are cooperative fees that are only paid once in a lifetime. “It’s eventually returned through loans for corn and fruit tree seeds,” he said. He also denied that farmers who do not pay are intimidated. “Some still have not paid it to this day.”

As to the purported PNBP, Saman said it was actually land and building tax (PBB) at Rp100,000 to Rp200,000 annually. He admitted to still keeping the PBB from farmers who are members of the KTH, because the money has not been collected by tax officers. Meanwhile, administrators of KTH Patiayam Rejo in a neighboring village claimed they have already submitted the PBB in the amount of Rp72 million.

In Rembang, a regency that neighbors Pati, Gema PS also assists KTH Gemah Ripah in Pasedan village, Bulu subdistrict. In this village, fees are calculated per square meter of the farmers’ land area, at Rp200 per square meter. According to Muhammad Mustain, 39 years old, the money is used by KTH administrators to pay for land measurement. The former KTH Gemah Ripah’s surveyor said farmers intend to apply for 150 hectares of social forestry on the Perhutani land.

Meanwhile, in Madiun, East Java, Asmadi, chairperson of the Batur Wono Joyo Forest Farmers’ Group in Pajaran subdistrict, has refused Gema PS’s assistance. The reason being, despite the various requirements being met, no IPHPS letter has been issued to this day. “They said it would be issued within a year,” he said.

Asmadi said for three years, each farmer spent at least Rp5 million for Gema PS’s assistance. “Not to mention, for gifts, souvenirs for Gema’s administrators, such as bonsai plants or timber logs every time they come here,” he said.

Like Saman, Siti Fikriyah Khuriyati claimed fees paid by farmers are for the benefit of the farmers. “Not to pay the ministry, but for costs such as transporting farmers, food, photocopies, organization documents required in applying for social forestry permits. They’re paying other people because many farmers are illiterate,” she said.

Fikriyah said not one cent of the money paid by farmers assisted by her organization has entered Gema PS’s account. All fees, including the surveying fee of Rp200 per meter, said Fikriyah, were determined based on an agreement with farmers. Furthermore, Fikriyah added, administrators have spent their own money when processing social forestry permits. “To be honest, administrators have worked hard. There is shame if the permit is not issued,” she said.

Besides Gema, large social forestry NGOs in Java include Semut Ireng. Suyanto, an activist with Semut Ireng, admitted that the farmer group that he facilitates collects fees from farmers. He assists the Mulyo Silayang Agroforestry Farmers’ Group in Randublatung, Blora, Central Java. Each farmer deposits Rp300,000. “All fees are for the interest of the KTH, based on an agreement,” he said.

KTH Mulyo Silayang is currently applying for a social forestry permit for a 350-hectare land. According to Suyanto, besides fees for the KTH’s members, there is an additional fee of Rp100,000 per plot of land, to pay Mitra Geo Survey Indonesia, which measures the social forestry land. “It took one month to measure,” said Lasdiono, KTH Silayang’s treasurer. “Not to mention photocopying the documents.”

Semut Ireng social forestry coordinator, Jundi Wasono, confirmed that a fee is collected from farmers with the KTH assisted by his organization. “But I forbid all Semut Ireng staff to enjoy the money,” he said.

Jundi also blatantly admitted that several KTHs that he has assisted have already collected the PBB and PNBP from farmers, for example, the KTH Patiayam Rejo in Pati and KTH Mbah Sariman Jaya in Blora. Both farmer groups have paid the PBB to the tax office at Rp72.6 million and Rp34.9 million, respectively, in 2021.

According to Jundi, the two groups paid the PBB and PNBP because they were billed by the tax office. Besides, he added, payment of both the PBB and PNBP are outlined in the IPHPS letter as the obligation of farmers who manage government forests. “The PNBP money is still with the group, we haven’t paid it to the tax office,” said Sundi.

Later on, Environment and Forestry Ministry’s (KLHK) Director-General of Social Forestry and Environmental Partnership, Bambang Supriyanto, issued a circular letter prohibiting various fees, including the PNBP. Jundi said the letter confuses him. According to Jundi, the instruction to collect the PBB and PNBP was a requirement of the IPHPS, which was signed by the minister of environment and forestry.

The prohibition Jundi referred to has to do with Bambang Supriyanto’s circular letters issued in June and August. In these letters, Bambang forbade KTH administrators or chairpersons to collect fees from members, including the PNBP. Bambang said the circulars were meant to put an end to fees in the field. “Such fees are not right and without basis,” he said. “They may be categorized as a general crime because they’re illegal fees.”

Despite such fees being illegal, the ministry has not sanctioned KTH or organizations that have been collecting fees. Bambang argues that no farmer, community member, or regional government has filed an official report with the ministry. “The regulation is clear: social forestry applications, verifications, until the permit is issued, are free,” he said.

The problem is, according to Siti Fikriyah, the forestry ministry does not have a budget for disseminating social forestry program. Such role is taken over by independent organizations, which require them to collect fees from farmers. Bambang Supriyanto said independent organizations may access donor funds to finance their assistance work. “We can endorse (the work),” said Bambang.

Siti Fikriyah and Jundi Wasono were colleagues with the Java Forest Joint Secretariat. The group of NGOs consisted of social forestry activists, including Semut Ireng, Omah Tani, and Yayasan Kehutanan Indonesia (Indonesian Forestry Foundation). They were volunteers who supported President Joko Widodo in the 2014 and 2019 general elections. These organizations often disagreed with Perhutani’s policies.

In 2018, all organizations in the secretariat agreed to form a new platform called Gerakan Masyarakat Perhutanan Sosial (People’s Movement for Social Forestry). The movement was disbanded a year later. Its founders created their own organizations. Fikriyah formed Yayasan Gema Perhutanan Sosial Indonesia, while Jundi joined Semut Ireng. “Our vision and mission no longer align,” said Fikriyah.

Jundi said the movement splintered not because of differences in its founders’ vision, but rather because of money issues related to rampant fees collected from social forest farmers. “Fees are not only occurring today. It has been around for a long time, including (fees collected) by Perhutani,” he said.

Fees by Perhutani staff were what prompted the government to revise its social forestry policy. Making use of the omnibus Job Creation Law, the government wishes to withdraw 1.1 million hectares from Perhutani’s area of 2.4 million hectares, to turn the land into special management forest areas (KHDPK). Social forestry program is one way to manage the KHDPK out of the six existing schemes.

Saman, Sukobubuk Village Chief and Chairman of the Hutan Sukobubuk Rejo Farmers Association. TEMPO/Erwan Hermawan

According to Bambang Supriyanto, although Minister of Environment and Forestry Siti Nurbaya has issued decision letter No. 287 on the total area of KDHPK in each province, the policy is not yet official because its technical and implementation guidelines are not fully ready. But, in the field, Gema PS administrators have already shared the KHDPK map.

In Kediri, East Java, for example, a KHDPK map of Manggis village, signed by Minister of Environment and Forestry Siti Nurbaya, is already in circulation. Siti Fikriyah confirmed the issue of the map, saying that Gema has created a KHDPK map for every location they assist, including in Manggis village. “We’re afraid that what we’ve advocated for years will not be included in the KHDPK,” she said. “For Kediri, (we have) already coordinated with Perhutani.

Bambang however said that Manggis village’s KHDPK map, signed by Minister Siti Nurbaya, is not legitimate. “It’s nonsense,” he said. The actual KHDPK map, said Bambang, has a scale of 1:2 million and was only published on the ministry’s website at the end of last week.

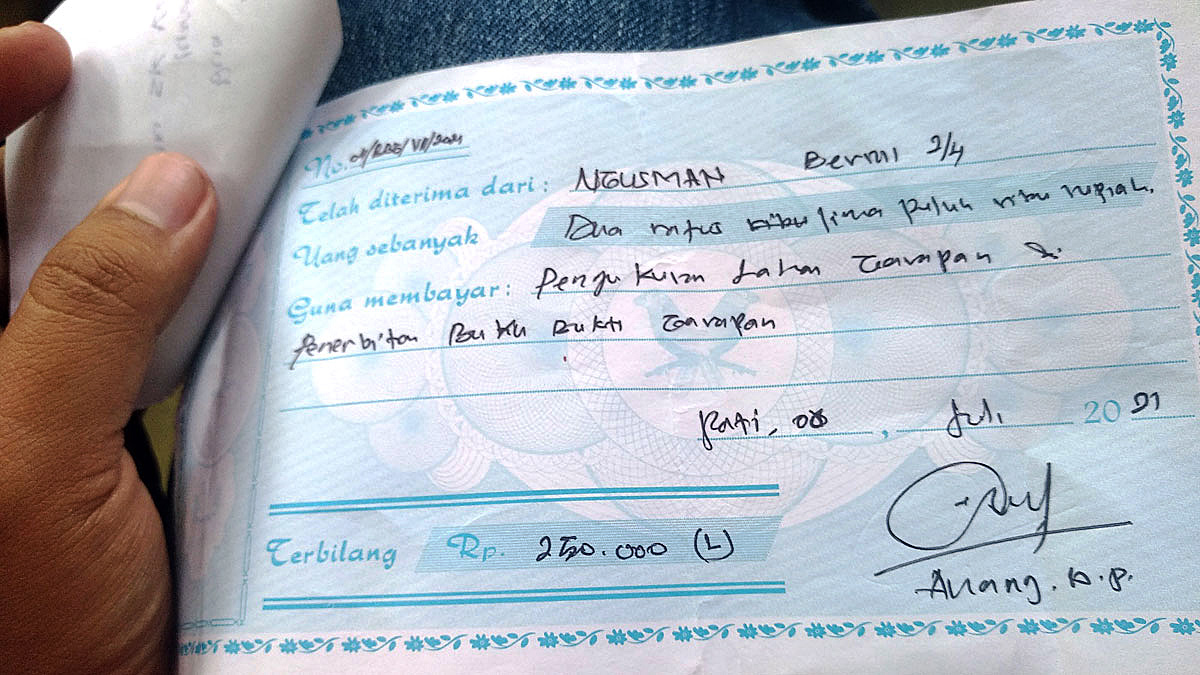

Receipt of a fee collection by the Wonosobo Forest Village Community Organization, in Puncel Village, Pati, that was assisted by Perhutani. Special Photo

According to Bambang, Perhutani have been collecting fees from social forestry farmers for a long time. Tempo managed to obtain numerous receipts of fees collected by local forest community groups (LMDH) under Perhutani’s assistance. LMDH administrators have collected Rp100,000 to Rp2 million.

In Manggis, the LMDH Adil Sejahtera asked farmers working on Perhutani’s land to pay Rp300,000 to Rp2.4 million. The receipts for these fees do not clearly explain its purpose, only that it was for profit-sharing. Referring to Minister of Environment Regulation No. 39/2017, IPHPS as well as kulin KK partnership document indeed set a profit ratio of 7:3 for revenues from forest commodity businesses, with farmers receiving 70 percent.

LMDH Adil Sejahtera Chairman Sudarno did not deny that such fees exist. According to him, the fees had already existed before he became chairperson in 2017. Furthermore, when he took office, Sudarmo said, he had to pay Perhutani a profit-sharing debt of Rp246 million. “We have the receipt of the transfer to Perhutani,” he said.

Receipt of a fee collection by the Hutan Sukobubuk Rejo Farmers Association in Pati, Central Java. Special Photo

Neither Perhutani’s Director of Human and General Resources and Information Technology, Muhamad Denny Ermansyah, denied that fees have been collected via the LMDH. But, he explained, fees are shared profit agreed upon by the LMDH and Perhutani, as stated in work agreements. He said farmers normally share 10 to 20 percent of their yields with Perhutani. “In principle, something must be given to the government,” he said.

Bambang Supriyanto said only tax officers can collect social forestry tax, not farmers nor KTH chairpersons. With the KHDPK, he said, the government hopes to resolve the mismanagement of forests in Java. “So that Perhutani can focus on its business instead of dealing with tenurial conflicts,” said Bambang.

Government Regulation No. 72/2010 on Perhutani states that its primary business has to do with timber and non-timber forest products. The regulation does not mention agricultural commodities. But, in various areas, Perhutani has been clearing forests for independent sugarcane programs. The deforestation has prompted protests from farmers because the state-owned enterprise means to take over the land they have been working on. In Grobogan, Central Java, for example, heavy machinery has entered land worked on by communities.

An invoice of a fee collection by the Hutan Sukobubuk Rejo Farmers Association in Regency, Central Java. Special Photo

In Puncel village, Pati, Perhutani’s management has cut down trees and installed stakes. Perhutani will be planting sugarcane on a 290-hectare land. Administrator of the Pati Forest Management Unit, Arif Fitri Saputra, said the sugarcane plantation was created to support sugar self-sufficiency in 2014. But, because of the farmers’ protests, Arif will reassess the sugarcane program.

More stories:

- Social Forest Free Riders

- Corporate Hand on Social Forestry Program

- A Thriving Forest Creates Economic Change

- Interview Director General Social Forestry Ministry of Environment

According to Denny Ermansyah, Perhutani had planned the sugarcane program prior to the KHDPK policy. Although decision letter No. 287 on the KHDPK was issued on April 5, sugarcane continued to be planted because the policy was not yet official. “But we are still coordinating with the environment and forestry ministry to support the program,” Denny added.

Meanwhile, Director-General of Social Forestry Bambang Supriyanto asks Perhutani not to hurry in planting sugarcane before the KHDPK map is published. He argues that the problem would grow complicated if farmers’ work areas, which fall under the KHDPK, are dismantled as KHDPK land is officially social forestry land. “Just wait, what’s the hurry,” he said.

This report is a collaborative work of Auriga Nusantara, Greenpeace Indonesia, Forest Watch Indonesia, and Hutan Kita Institute, Jaringan Pemantau Independen Kehutanan, Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia, Eyes on the Forest, Anti-Illegal Logging Institute, Perkumpulan Elang, Kelompok Advokasi Riau with the support of the Rainforest Investigations Network Pulitzer Center

INVESTIGATION TEAM

Team Head:

Bagja Hidayat

Project Leader:

Mahardika Satria Hadi

Writers:

Erwan Hermawan, Mahardika Satria Hadi, Dini Pramita, Aisha Shaidra

Editor:

Bagja Hidayat

Contributors:

Harry Tri Warsono (Kediri), Nofika Dian Nugroho (Madiun)

Designer:

Rio Ari Seno

English Editor:

Luke Edward

Photo Researcher:

Ratih Purnama