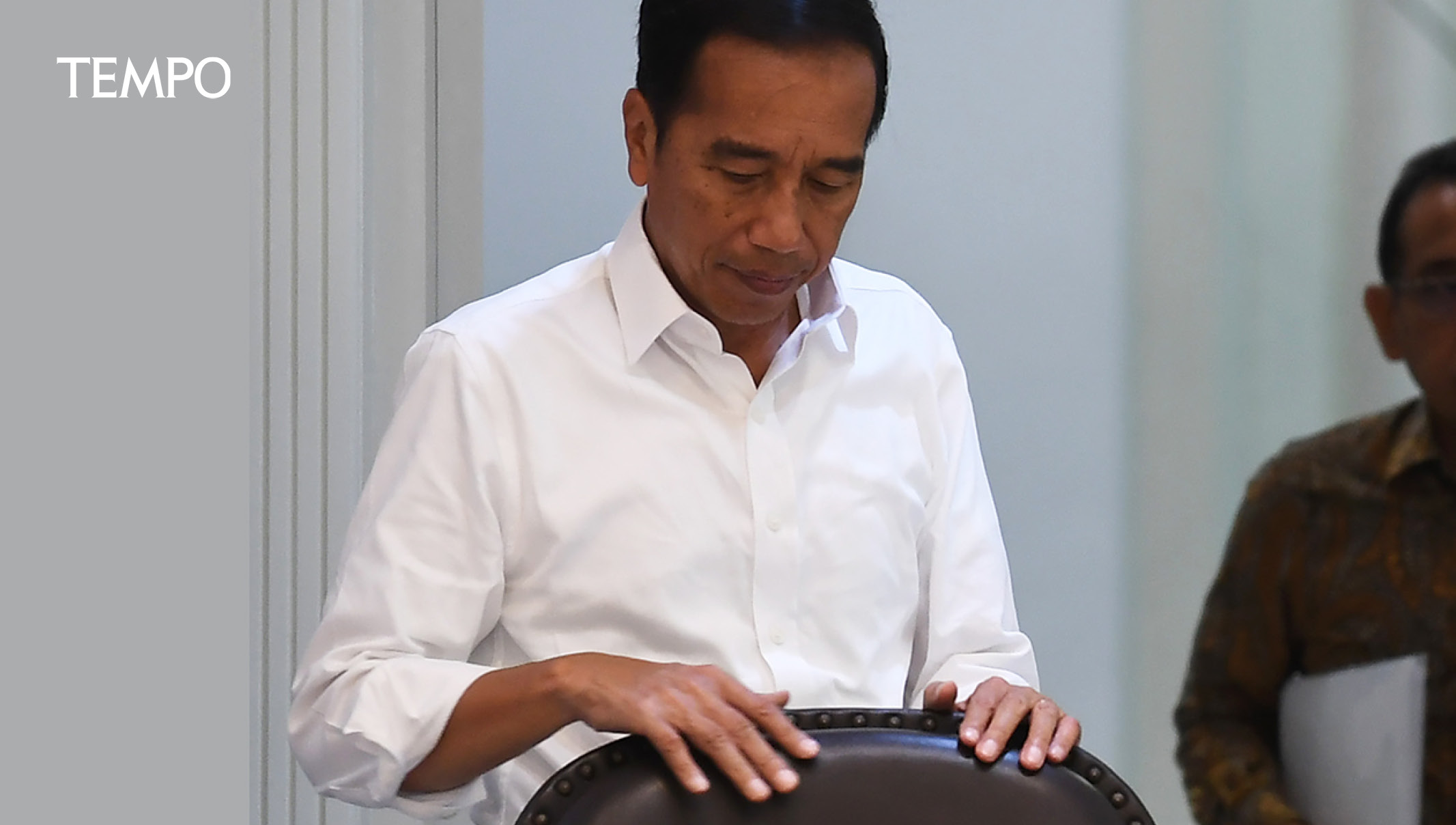

Jokowi’s Fear of Retirement Syndrome

Jokowi passed a number of strategic policies at the end of his administration. Making the president-elect a hostage to fortune.

Tempo

October 7, 2024

JOKO Widodo is not Imran Khan, the Prime Minister of Pakistan from 2018 to 2022, who was jailed for leaking state secrets. But in one sense, perhaps they have something in common: they are both populist leaders trying to maintain their popularity and influence at the end of their terms of office, and maybe afterwards.

Tehreek-e-Insaf, Imran Khan’s party, won the general election in Pakistan in February 2024, while Imran was in jail. Jokowi’s term of office will end on October 20, and he will not go to jail. But his interventionist practices—as well as his many tours around the country to boost his popularity—have convinced many people that he does not want to lose his grip on government in the future.

In the last few months of his presidency, he has done many things that should not be done by a president approaching the end of his term. For example, he dismissed ministers who did not support the electoral coalition that brought about victory for the pairing of Prabowo Subianto and Gibran Rakabuming Raka, his son. He created new positions in cabinet: the National Nutrition Council and the Presidential Communications Office. He intervened in the naming of prospective commissioners of the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK).

In the first of these steps, it seems like he wanted to give the impression that he was ‘safeguarding’ the new government: he fired Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) politicians from the cabinet. The PDI-P is the only party that has not joined the Indonesia Onward Coalition Plus, after the Nasional Democrat (NasDem) Party, the National Awakening Party (PKB) and the Justice and Prosperity Party (PKS), which also did not support Prabowo during the election, finally joined. The replacement of Justice and Human Rights Minister Yasonna Laoly from the PDI-P with Gerindra Party Politician Supratman Andi Agtas, for example, was done to ensure that the approval of laws from a number of ministries was not obstructed.

The formation of these new bodies in the cabinet may have been for the same aim: to smooth the way for the president-elect. Although this looks like a good thing at first glance, Jokowi is in fact dictating Prabowo. Given his position as one of Jokowi’s ministers, it is difficult to imagine that Prabowo will have a voice in decisions about replacing cabinet ministers. After his inauguration on October 20, it is easy to imagine how awkward Prabowo will be with the new posts and officials established by Jokowi.

This intervention caused increasing problems with the selection of KPK commissioners for the 2024 to 2029 period. Jokowi began the KPK selection process in May by establishing a selection committee dominated by people close to the Presidential Palace. Beginning with registration and ending with the final selection at the end of September, Jokowi approved 10 candidates from the selection committee, whose names were then passed on to the House of Representatives (DPR). These candidates will take part in a fit-and-proper test, and from them, five commissioners will be chosen.

The authority to select the new leadership of the KPK should have lies with Prabowo Subianto. The reason given by the Palace, that the new president will not have much time, so Jokowi made the decision for him, is a contrivance and potentially a violation of the law.

Constitutional Court Ruling No. 112/PUU-XX/2022 added the term of office of KPK commissioners from four to five years, meaning that the current commissioners’ terms will only end in December. Three months is plenty of time for Prabowo to make his selections.

It is fair to consider Jokowi’s efforts to force an acceleration of the KPK leadership’s selection process as an effort to safeguard him and his family once he is no longer president. Having served two terms dogged by allegations of transgressions, Jokowi is worried about losing control of the KPK.

As a lame duck president, Jokowi should not be making strategic decisions. This is to ensure that a new president has the freedom to run his or her administration without being held hostage to last minute decisions from his or her predecessor.

Jokowi must show some respect for the president-elect if he does not want to be labeled as suffering from post-power syndrome.