Ambiguous Levies in Bali

Monday, January 27, 2025

Customary village officials in Bali appoint pecalang to collect fees from visitors. The Corruption Eradication Commission and the Indonesian Ombudsman once intervened.

arsip tempo : 174556275026.

ALTHOUGH born and raised in Bali, I Ngurah Suryawan regularly pays a contribution to the customary village where he resides in Denpasar. The money is collected by the pecalang, traditional security officers in customary villages, every month. Currently, the total amount collected from him and his wife is Rp60,000 (around US$3.7). “The amount keeps increasing,” said the anthropologist from the University of Warmadewa in Denpasar to Tempo on Thursday, January 23, 2025.

Despite being the provincial capital, Denpasar still has customary villages. A customary village is a form of traditional governance separate from urban villages, or as they are more commonly known in Bali, ‘desa dinas.’ The fee or contribution is called dudukan. In the village where he lives, I Ngurah is classified as a krama tamiu. This status is given to Hindu Balinese people who come from other customary villages. He has lived in the customary village in Denpasar since 2012, and since then, he has had to pay dudukan.

The collection of dudukan has been going on for a long time in Bali. The issue is that this levy also targets groups that do not have an income, such as students. Doni, an alumnus of Udayana University in Denpasar, originally from Jembrana, admitted that he was asked to pay a dudukan of Rp15,000 (US$0.92) per month while renting a room in South Denpasar in 2019. The pecalang in that village collected the fee.

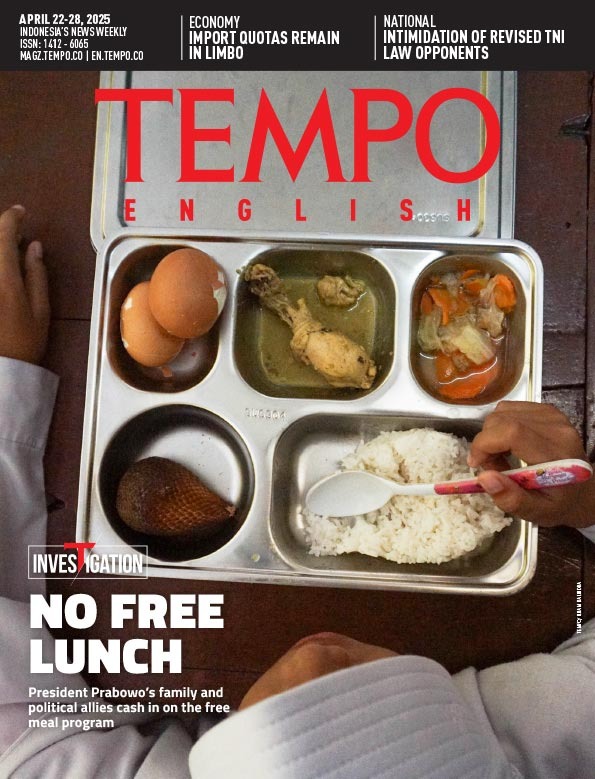

Putu (second from left), with his fellow pecalang during a traditional ceremony in Sesetan Traditional Village, Denpasar City, January 17, 2025. Tempo/Fajar Pebrianto

A similar experience was shared by Ranny, a student from outside Bali at Udayana University. One day, Ranny said, the pecalang knocked on her boarding house door at 7pm just to ask for a dudukan fee of Rp15,000. Not wanting the matter to drag on, Ranny paid for four months in advance. Both Ranny and Doni never received an explanation about the purpose of the levy, nor did they receive any proof of payment.

It turns out that this fee is also collected from shops and small businesses. This practice still continues today, with varying amounts collected in each traditional village. For example, in Denpasar, some pay Rp40,000 (US$2.4) per month, while others report paying Rp5,000 (US$0.30) per day. However, there are also those who are not subjected to any fees.

Currently, there are 1,500 traditional villages on the island of Bali. These villages are divided into 3,600 banjar (community groups under the traditional village). The largest number is in Tabanan Regency with 349 traditional villages, while the least is in Denpasar City with 35 villages. Each traditional village has special autonomy to implement its customary laws. This is why the collection of dudukan can differ from one village to another.

Gede Indra Pramana, a lecturer at Udayana University who also lives in Denpasar, said he has never paid dudukan. Although he resides in a traditional village, the banjar in his village does not collect dudukan fee. This is despite that he has the krama tamiu status. Even though he was born in that traditional village, he is still considered a newcomer. “Because my ancestors came from another traditional village," said Gede Indra.

In many places, the collection of dudukan has been going on for years. However, many Balinese people still do not understand the rules surrounding the fee in traditional villages. Complaints about the fee are often found on the website https://pengaduan.denpasarkota.go.id/, a complaint portal managed by the Denpasar City Government.

From Tempo’s investigation, it was found that those who do not understand dudukan are generally from outside Bali. They come to work in Bali, and some even have Balinese identification cards. Some admitted to paying the fee directly to the pecalang every month, while others refused to pay.

A pecalang in the Sesetan Customary Village, Denpasar City, who requested to be called Putu, said he is used to facing village residents who refuse to pay dudukan. When this happens, Putu and his fellow pecalang try to explain that paying the dudukan fee is a customary village policy.

Residents take part in the Ngaben cremation ceremony in Sesetan Pekraman Village, Denpasar, Bali, October 11, 2024. Cittavagga/Shutterstock

Putu said that the collection of dudukan is still ongoing today. He explained that the levy is part of the community’s contribution to maintaining security in the customary village. In the Sesetan village, there are 38 pecalangs. Their duties are similar to those of residents who implement the neighborhood watch system or siskamling. “We gather in the banjar at 1am, patrol, and return at 5am,” he explained.

The Head of the Bali Provincial Department of Traditional Community Empowerment, I Gusti Agung Ketut Kartika Jaya Seputra, admitted that the collection of dudukan is still an issue today. The goal is to maintain the sanctity and security of each area. The problem is that the collection of dudukan must be regulated. This is why the government issued Regional Regulation No. 4/2019 on Traditional Villages. They are working to streamline the collection of dudukan. “We don’t want traditional villages to be labeled as collecting illegal fees,” he said.

•••

FOR the Balinese people, traditional villages are an ancestral heritage that must be upheld. The Chair of the Bali Provincial Traditional Village Council, Ida Pangelingsir Agung Putra Sukahet, stated that traditional villages are the first line of defense in preserving the noble customs and culture of the Balinese community. “And they are the last line of defense,” he added.

A customary village has three main elements: parahyangan (relationship with the divine), pawongan (relationship with society and the environment), and palemahan (relationship among the community members). These three elements represent the Tri Hita Karana, the philosophical foundation of Balinese Hinduism. The activities in the customary village that embody these three elements undoubtedly require funding.

Every year, the provincial government allocates Rp300 million (US$18,520) to each traditional village. The main purpose of this funding is for religious ceremonies, or parahyangan. For other purposes, such as maintaining security and cleanliness in the pawongan and palemahan domains, traditional villages collect contributions from the local community. This is the origin of the dudukan fee. “So, for example, religious ceremonies should not use dudukan funds,” explained I Gusti Agung Ketut Kartika Jaya Seputra.

In addition to being collected from krama tamiu, this dudukan is also levied from tamiu, the term for non-Hindu Balinese newcomers or outsiders. Meanwhile, the original residents of a village are called krama desa adat. They are also subject to a levy known as paturunan. These three types of krama are known as the inhabitants of a village within Bali’s customary system.

Although they collect levies and receive financial aid from the government, villages continue to face financial challenges. Some villages still struggle to cover all the costs of religious ceremonies, even though they have received a subsidy of Rp300 million from the regional government. The financial burden is heavier for customary villages with few banjars and residents.

Officers collect data on non-permanent residents in Tanjung Benoa Village, Badung, Bali, November 8, 2023. Foto: Kelurahantanjungbenoa.badungkab.go.id

The issue of inadequate funds for customary ceremonies has become a subject of gossip in Bali. The Chief of the Sesetan Customary Village in Denpasar, I Made Widra, is among those who have heard about the issue. He acknowledges that the subsidy problem has been a topic of discussion among various groups. “There have been suggestions for a more proportional allocation of funds,” he said.

The ability of customary villages to pay pecalang also varies. The Chief of the Panjer Customary Village in Denpasar, Ketut Oka Adnyana, stated that the village can only afford to pay Rp50,000 (US$3.08) per day for each pecalang on duty to maintain the security of the adat village. “For instance, if they work four times a month, they only receive Rp200,000 (US$12.3),” Ketut explained.

A lecturer and resident of Denpasar, I Ngurah Suryawan, who is required to pay the fee, understands that this levy is essentially a response from Bali and customary villages to survive amidst the changing times. Newcomers and economic activities in the village are considered as potential sources of income for villages, which are increasingly pressured by outside investments. “Although I am Balinese, I am critical of this levy,” said the author of the book Bali, Narasi dalam Kuasa: Politik dan Kekerasan di Bali (Bali, Narratives and Power: Politics and Violence in Bali).

Moreover, the potential for misuse remains. He cited the case of I Ketut Riana, the Treasurer of the Berawa Customary Village in North Kuta, Badung. In October 2024, I Ketut Riana was sentenced to four years in prison and a fine of Rp200 million (US$12,340) by the Denpasar Corruption Court for extorting investors up to Rp10 billion (US$617,300).

The Balinese government is aware that the implementation of this levy must be regulated. That is why, after the issuance of Regional Regulation No. 4/2019, Governor I Wayan Koster issued Bali Governor Regulation No. 34/2019 on the Management of Customary Village Finances in Bali. “This was the legal basis for the dudukan,” said I Gusti Agung Ketut Kartika Jaya Seputra.

News of the dudukan levy on newcomers and business owners also reached the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK). To discuss this matter, in May 2022, KPK’s Director of Prevention, Pahala Nainggolan, and his team flew to Bali. The result was that the KPK recommended that the fee be implemented with clear guidelines through regulations. “The key point is to regulate transparency in the collection, management, and accountability of the funds collected,” said Aminudin, Director of Anti-Corruption at KPK’s Business Unit.

Five months later, in October 2022, I Wayan Koster issued Bali Governor Regulation No. 55/2022, which now serves as the legal basis for the collection of dudukan. This regulation was created based on KPK’s recommendation.

The Customary Village Council (MDA), a pasikian or association of customary villages in Bali, also realizes that the collection of this fee has caused issues in the field. A series of problems are noted in a decision document from the MDA, such as objections to the fee amount and the lack of ethics among the fee collectors, i.e., the pecalang, who are considered impolite.

Not all villagers are involved in discussions about dudukan. The Chairperson of the Bali Province Customary Village Council, Ida Pangelingsir Agung Putra Sukahet, shared that reports on the fee are only discussed in meetings attended by the krama desa adat. “It could involve thousands if krama tamiu and tamiu are included,” Ida said.

However, the council continued to adjust. In December 2022, the MDA issued a decision on guidelines on the writing public welfare regulations in customary village areas. “The goal is to ensure that dudukan collection does not conflict with the law,” said Ida.

Tanjung Benoa Beach, a tourism site in Badung, Bali, April 5, 2013. Tempo/Subekti

Both regulations require customary villages to update their awig-awig and pararem. Awig-awig is the highest customary law rule in each customary village that has been followed by the Balinese people for generations. Pararem are the derivative regulations of awig-awig. These rules are made to ensure that the dudukan collection aligns with KPK’s recommendations.

In March 2023, 11 members of the Bali Ombudsman Representative team visited 21 customary villages in Denpasar, Tabanan, Badung, Klungkung, and Gianyar. It turns out that the Ombudsman also became a place for the people of Bali to complain about dudukan. After collecting information for about six months, the Ombudsman found several issues.

It appears that the MDA’s decision issued in December 2022 had not been implemented in all customary villages. Some villages were even unaware of the new guidelines for dudukan collection. Out of 1,500 customary villages, only one had a pararem on dudukan and was registered with the Traditional Community Advancement Office.

The village in question is the Tanjung Benoa Customary Village, Kuta, Badung. The pararem regulating dudukan was created after the Chief of the Tanjung Benoa Customary Village, I Made Wijaya, was tried in 2019 at the Denpasar District Court for collecting illegal levies on business owners in his area.

To ensure that the pararem regulating dudukan is legally implemented, customary villages need verification from the MDA and registration with the Customary Community Advancement Office. The pararem must then be announced to the public. This is because customary villages cannot collect the fee unless there is a pararem regulating it.

The Ombudsman team also encountered other obstacles. The limited human resources in traditional villages often hinder the formation of pararem. As a result, the process is delayed. “Therefore, the Ombudsman encourages the establishment of a timeframe to ensure certainty in service," said the Head of the Bali Ombudsman Representative, Ni Nyoman Sri Widhiyanti.

From Tempo’s investigation, some villagers who are asked to pay dudukan actually have no objection to paying. However, they want clarification regarding the benefits and intended use of the funds. Unfortunately, even though efforts to regulate the legal basis for this fee are still incomplete, the collection of dudukan continues to this day.

I Ngurah Suryawan still routinely pays Rp.60,000 to the customary village each month. He hopes that all villagers will be able to access accountability reports for those levies. Such an effort is plausible considering the current level of technological development. "Customary villages must be able to adapt to technology," he said.

I Ngurah Suryawan also continues to pay Rp60,000 every month to the customary village. Ngurah hopes that all villagers can access reports on the accountability of the collected levies. With the current technological advancements, this can be done. “Customary villages must be able to adapt to technology,” he said.