The Return of Meat Import Quotas

Monday, February 26, 2024

The government, once again, is applying a policy of import quotas. This will lead to collusion and bribery.

arsip tempo : 174661981267.

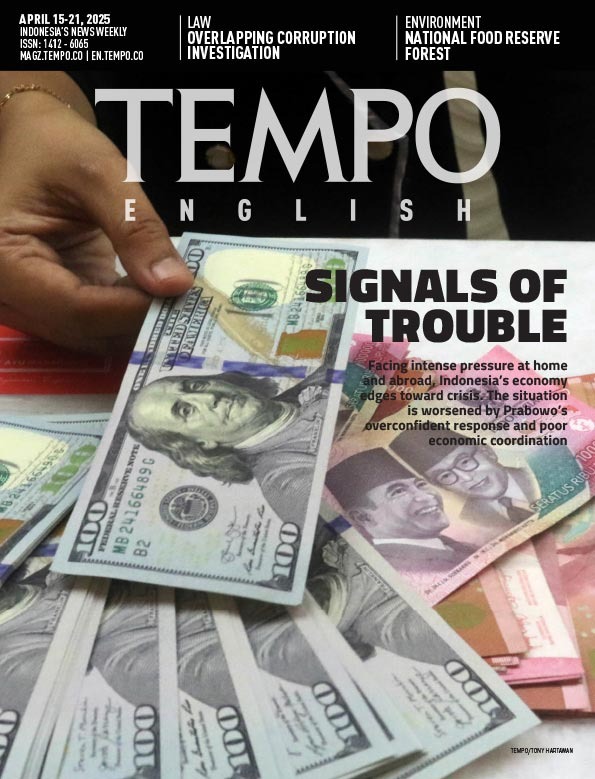

THE decision by the government to use a quota system in allocating meat imports is a step backward. Instead of guaranteeing domestic supplies, this system will once again become an arena for bribery on the buying and selling of quotas.

The return of the quota system in the allocation of beef imports was decided at a coordination meeting held by the Coordinating Ministry for the Economy in the middle of December last year. According to the minutes of the meeting, the allocation for beef imports in 2022 will be 140,951 tons for 56 importers. This policy supersedes the regulation, ending the import quota that had been in force since 2013.

In his decision, Coordinating Minister for the Economy Airlangga Hartarto allocated import quotas of 100,000 tons of buffalo meat from India and 20,000 tons of buffalo meat from Brazil to the State Logistics Company (Bulog) and Berdikari. ID Food was also awarded an import allocation of 7,000 tons of beef.

There is no strong basis for the distribution of those quotas to importers. For example, Bulog has yet to distribute 50,000 tons of imported meat to markets, but has obtained a new quota. The same is true for Berdikari, which only imported 0.03 percent of its import target last year, but that has been awarded an import quota of 100,000 tons for 2024.

The government’s justification for giving import quotas totaling much less than the domestic demand, namely to spur on the domestic livestock industry, is contrived. For a long time, the cattle farming sector in Indonesia has grown very slowly because of the shortage of high-quality breeding cattle, poor productivity and a low-quality business system. As a consequence, the nation is highly dependent on imported beef to meet demand.

At present, the domestic beef demand is 2.6 kilograms per person, of which only half can be met from domestic production. The remainder must be imported from various nations. If this year’s imports of 141,000 tons are procured at a price of Rp140,000 (around US$9) per kilogram, the total value of the business that importers are trying for a share of will be Rp19.74 trillion (US$1.26 billion).

This tempting business involving huge sums of money often turns into an arena for rent seekers, corrupt officials and dirty politicians. In 2011, the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) uncovered an import buying and selling racket at the Ministry of Agriculture involving Justice and Prosperity Party (PKS) President Luthfi Hasan Ishaaq and Indoguna Utama, a major beef import company. Luthfi had been taking advantage of this scheme after a member of his party was appointed Agriculture Minister.

It is almost certain that the reimposition of the quota system will disrupt the domestic supply chain, which could in turn lead to a rise in the price of beef. Even in a system without quotas, importers need almost a year to obtain approval and bring in imported beef. With this additional import culture regulation, the input process could become longer and more complicated.

However, Ramadan (Islamic fasting month), which always sees a sharp rise in the demand for beef, is approaching. It is not impossible that the price of beef in the markets will soar, exceeding the maximum retail price of Rp130,000 (US$8.33) per kilogram. Hence, it is understandable that the move to reimpose quotas, which were already banned by the World Trade Organization, has led to suspicions that some individuals trying to make profit behind this quota scheme. This is clearly a state capture corruption, a type of corruption facilitated by regulations.