A Strike at the Heart of Our National Data

Monday, July 1, 2024

The hacking of the National Data Center is a threat to the personal data of millions of people. The government fails to establish a digital security system.

arsip tempo : 174459507326.

THE government’s confusion about how to deal with the collapse of the National Data Center after it was hacked is the result of a mistaken paradigm. Instead of granting the public the right to the protection of their personal information, the government has seen the Internet simply as a national security problem.

A virus penetrated the Temporary National Data Center (PDNS) in Surabaya, East Java, on Thursday, June 20. The government had no idea how to deal with this and only officially announced it four days later, after prevaricating by claiming the disruption was only a technical problem.

On the first day, ransomware brought down the services of 347 central and regional government institutions. The most serious disruption was at the Immigration Directorate-General. This resulted in long lines of airplane passengers at arrivals and departure gates because immigration checks had to be done manually.

The Communication and Informatics Ministry, manager of the PDNS, as well as the National Cyber and Encryption Agency (BSSN) did not have any crisis protocols in place when the attack occurred. The mutual accusations of blame for responsibility considerably slowed down their response to the attack. It also led to speculation about the cause: from negligence in maintaining the system to a counterattack by managers of online gambling websites.

The BSSN said that the attack on the PDNS was carried out by hacking the computer system and installing malware aimed at extortion. The hacker, who has not yet been publicly named, installed a newly developed ransomware named Brain Cipher (Brain 3.0 ) and asked for a payment of Rp131 billion.

At the same time as the PDNS was paralyzed, the National Police Automatic Finger Identification System and the Indonesian Military Strategic Intelligence Agency were also hacked. Important data belonging to the two institutions was then offered for sale on an Internet site not accessible by ordinary search engines or browsers. The motive was the same as that of the hacker named Bjorka, who offered the data of 34 million Indonesian passport holders for sale.

The poor coordination between the Communication and Informatics Ministry and the BSSN was one of the triggers for this attack. The BSSN claims that they already gave a warning of potential hacking, referring to similar incidents in many other countries to the Communication Ministry. However, this warning was not responded seriously. On June 17, the BSSN found an attempt to deactivate the PDNS security features that made it vulnerable to virus attacks.

Unfortunately, the Communication Ministry did not manage the PDNS well. It turns out that only two percent of the data was backed up, making it difficult to quickly recover the hacked data. This is strange because in 2022, the Ministry issued a tender for backing up the data, which was won by Energi Jaring Komunikasi. This means that it is fair to suspect that the tender winner did not do its job.

The lack of readiness of the government in its response to this digital attack might be a violation of Law No. 27/2022 on Personal Data Protection. Article 46 clearly states that if there is a failure to protect personal data, the manager of this data must report in writing to the individuals and the personal data protection agency within 72 hours.

Another indication is that the government’s lack of attention regarding the provision of security guarantees was apparent from the fact that no technical implementation regulation relating to the Personal Data Protection Law has been issued, despite this having been mandated by that law since 2022.

This is worrying at a time when Indonesia finds itself in a cybersecurity emergency. According to the BSSN, there were 279.8 million cyber attacks against Indonesia in 2023. The previous year there were 370 million, and it is estimated the total number will rise this year. Because of this, global cyber security company SEON ranks Indonesia’s digital security at number 62 of 93 nations, far below Malaysia and Singapore.

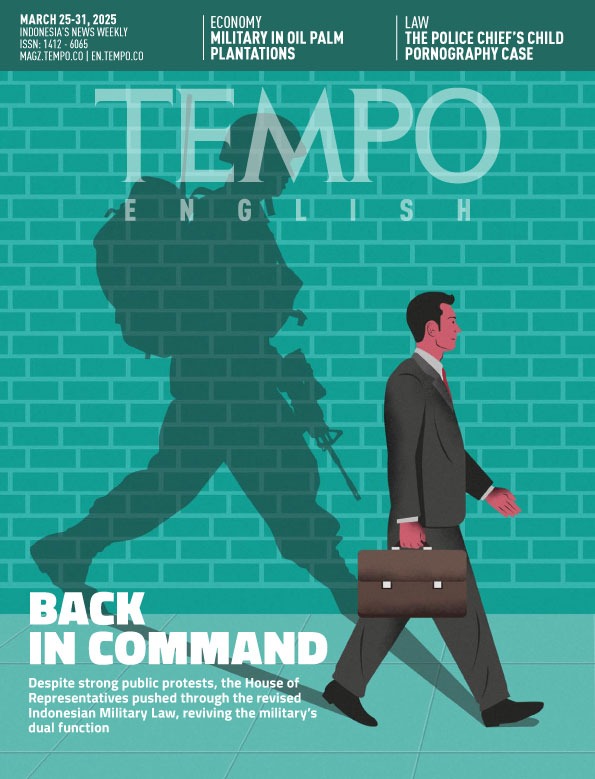

The failure of Joko Widodo’s administration to establish a digital security system should serve as a lesson for Prabowo Subianto, the president-elect. Aside from thinking about purchasing key military equipment, Prabowo should also strengthen our digital security system.