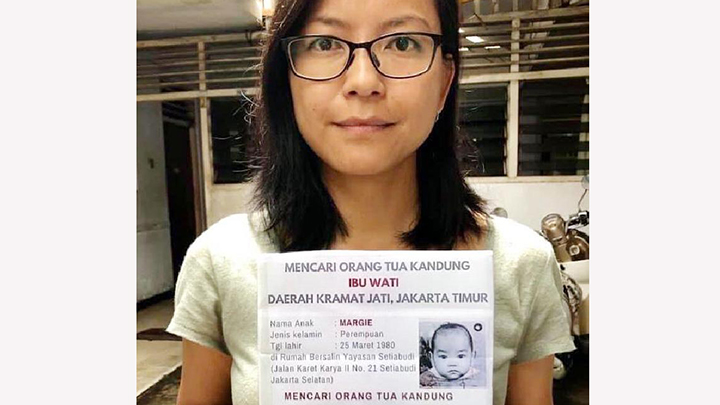

Seeking Roots All the Way to Nongkojajar

Monday, March 1, 2021

The Netherlands halted international adoption after cases of child trafficking came to public light. Many adopted children from Indonesia have not been able to find their biological parents.

arsip tempo : 174429055357.

THE house on Jalan Mohammad Toha Kilometer 18 No. 9, Pondok Cabe Udik, Pamulang, Tangerang, Banten, looked quiet from the outside. The Loka Kasih children’s home, which assisted in the adoption of children by Dutch families, used to operate here. On Thursday, February 18, the house on the Jakarta-Bogor main throughway seemed desolate with its closed gate and overgrown vegetation.

According to Mujianto, a marine veteran, a cooperative marin

...

Subscribe to continue reading.

We craft news with stories.

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More

For the benefits of subscribing to Digital Tempo, See More